I was wondering what to post about this morning, having been finally and rudely evicted from my bed by the Archers omnibus (a UK radio programme about rural life in England, which I loathe for its pantomime script and ham acting), and have decided to begin at the very beginning, as far back as we can trace the history of the parcel of land we are about to regenerate for urban agriculture. Many years ago, when V and I first saw the site at Barlow Road, in Wednesbury North, and mentally noted its potential, while we set about developing out two other community farms and gardens, I noticed that a sad scrap of internal hedgerow was probably very old and likely to have marked out a long lost field boundary. I went to the archives at Smethwick Library, partly to find out about industrial development in the area that may have left a legacy of land contamination (Sandwell is redlined as a contaminated area), and partly to find out the patterns of land ownership.

I was wondering what to post about this morning, having been finally and rudely evicted from my bed by the Archers omnibus (a UK radio programme about rural life in England, which I loathe for its pantomime script and ham acting), and have decided to begin at the very beginning, as far back as we can trace the history of the parcel of land we are about to regenerate for urban agriculture. Many years ago, when V and I first saw the site at Barlow Road, in Wednesbury North, and mentally noted its potential, while we set about developing out two other community farms and gardens, I noticed that a sad scrap of internal hedgerow was probably very old and likely to have marked out a long lost field boundary. I went to the archives at Smethwick Library, partly to find out about industrial development in the area that may have left a legacy of land contamination (Sandwell is redlined as a contaminated area), and partly to find out the patterns of land ownership.

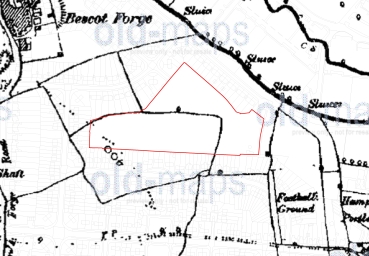

What we found out was that this sad scrap of land was once owned by a Rowntree, the famous former chocolate manufacturers and Quaker family, that did try to bring about better living conditions for people in Birmingham in the darker days of industrialisation. We found the old pattern of field boundaries, and when you overlay the boundaries of the site (see pic), you can indeed see the field boundaries, and we can verify that the fragment of hedgerow can be dated to at least 1880, and is probably much older than that, perhaps dating back to the enclosures, when people were evicted from their ‘commons’, often being forced to migrate to find work in the emerging industrial centres as factory fodder – a pattern now being repeated in poorer parts of the world, but that’s for another blog on another day.

This land parcel, amazingly, this scrap of relatively unadulterated farmland, survived the most intense explosion of industrialisation of its time, at the birth of the industrial revolution, where mining and metalworking were first transformed from craft industries to fully industrialised, large scale technologies, which gobbled up the land and drew in a major urban population of industrial workers. All around were pit and opencast mines, blast furnaces, metal fabricators, chain makers, engine builders, and associated industries. The Black Country’s products fuelled the development of the modern industrial world. As the years progressed, the literally blasted landscape was left in ruins as centres of industrialisation moved on, and capital took flight, and industrial scale landfill and major transport networks took over the area. It was Margaret Thatcher’s regime, with its visceral hatred of organised labour, that finally did for the place, in the 1970s, since then there has been little hope of recovery for the area and its inhabitants.

I can’t begin to describe the ugliness of this particular swathe of the Black Country, with stilt-raised motorway networks and intersections (not to give the motorists a better view, but because the land is unstable), rail shunting depots, acres of old and decaying, and newer, industrial infrastructure. As for the site itself, to the north is an immense landfill site – now home to a fairly new ‘build ’em long and low on concrete rafts’ big box stores and Birmingham IKEA, with who-knows-what buried there; to the east are two high schools, most probably on landfill or old industrial sites; and not far beyond this is the 24/7 roar of one of Britain’s busiest, most congested motorways. The stream that once ran to the north boundary (now buried under the stores) was once the most significant source of copper pollution in the area.

In amongst all of this, and housed on a estate that was built in the 1920/30s, which in part surrounds the fragment of farmland that forms the Barlow Road site, are the good people of Wednesbury, struggling as always to survive – a million miles away in economic and social terms from the middle and upper classes of Britain. Having previously worked mainly in the south of the borough, we are now just getting to know Wednesbury’s YamYams (a Black Country term). We are beginning to explore local social networks and associations, and we are told that these are particularly strong, with a community of folk that will go a long way to help each other. I can’t help but wonder to what extent these strong local associations developed in response to the poor economic, social, and environmental, living conditions people have endured. It takes me back to my roots in the back streets of Brixton in south London, where people were poor, died in droves of (now) preventable diseases, but stuck together and helped each other in hard times.

So, how come this little gem of the old world of farming survived, and not only that, remained as a site of food production for the community? As far as we can make out, it was gifted by the owner to a local steelworks, to act as an allotment site for the employees, so that they could grow food for their families. The allotments tradition is still strong, if largely invisible, in Sandwell and across the UK. Some say it was less about filling stomachs and more about keeping the men out of the pubs and saving souls, and others will argue that it was a way of keeping industrial wages low, but ensuring that your workforce was fit to work; both probably true. Then, when the steelworks closed, it was passed to the Council as a statutory allotment site and protected green space, where it fell into disuse over many years as the art and practice of allotment keeping declined.

Which is good for us, and good for the now thriving allotment community that have battled the dereliction on their portion on the site, and brought it back into production. Now it’s our turn to tackle the dereliction and fly tipping on the remaining three or so acres. It will be a major, and expensive, job, funded by charitable trusts. It has been a two-year effort to raise the funds to restore this forgotten and unloved historical gem to productivity, and to restore the fragment of hedgerow to something resembling what it may once have been. This scrap of land has the potential to bring into full view a timeline of the history of the area and its people, something we will be celebrating as we transform this hidden gem of the old world of farming, trapped in a mixed up, mashed up industrial space: a small ‘space of hope’ for the local community.

What a fantastic history lesson! Hope you can do something to maintain land in local ownership. All the best. Fran

Thanks Fran – lots of love to you

I had a look at the Barlow Road site, it has a lot of potential.

Pingback: » Wednesbury History in brief A Zillion Ideas and counting…

Pingback: Wednesbury History in brief « Mike10613's Blog